Log4j vulnerability (aka CVE-2021-44228) is one of the most significant vulnerabilities in a decade. Which is saying a lot when you hold it up against prominent issues like SolarWinds.

From the moment of disclosure on Friday, December 10th, the Internet has become a scanning zone for Log4j vulnerabilities. Every publicly addressable IP is being scanned. Bad actors are looking for vulnerable systems to infiltrate. Defenders are looking for vulnerable systems to patch. While the focus has been on systems exposed to the Internet side, the reality is that many Log4j vulnerabilities will also be visible from inside the network and accessible by both adversaries and insider threat actors. In other words, ignoring vulnerabilities not accessible from the Internet is not a sound strategy; these will likely be found and exploited.

Having deception decoys placed in your environment can serve as an early warning system. It helps quickly identify attackers in your environment as they scan for this vulnerability. Specifically, deception technologies like Fidelis Deception® can help protect organizations from zero-day threats before they are published, and before patches or rules are updated. No need to design, configure and tune new rules; once deception is turned on, it can detect the attackers trying to exploit the vulnerability with a near-zero false positive rate.

The Fidelis Threat Research Team has been tracking these scans on both our customer networks as well as public-facing decoys spread out around the world. Alerts from these decoys are useful in understanding the extent that Log4j is being exploited. In this blog, we provide an overview of some of the findings from these decoys related to the Log4j CVE.

Deception as an Early Warning System

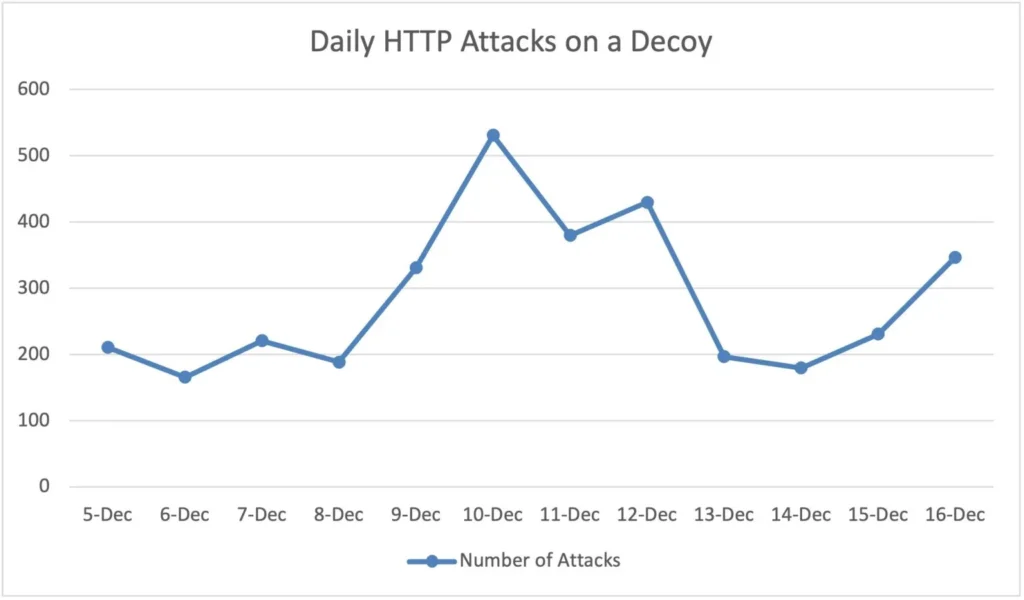

We started by taking a deep look into all HTTP-based attacks on internet-facing decoys. We then sorted regular HTTP attacks (which create a baseline of Internet ambient noise from continuous opportunistic scans) from the attacks attempting to exploit the Log4j vulnerability by analyzing the attack data (headers, URLs, etc.).

Our public-facing decoys started to receive attack attempts related to the Log4j CVE on Friday, Dec 10 – minutes after the CVE was first published. This is the normal vulnerability release cycle behavior. After vendors publish a vulnerability, threat actors jump on it trying to exploit, while defenders play catch up to install patches. The window of vulnerability is the time between when the CVE is published and when it is patched by an organization. Threat actors typically have several months to run their attack campaigns because patching enterprise software typically involves change management and operational impact assessments.

Monitoring the HTTP-based attack attempts over the past week, we witnessed a peak of attacks on December 10, but not an overall significant increase in the number of attacks over time. The first graph shown below is the number of HTTP based attacks on one of the public decoys.

To prove detection efficacy, once the CVE was released, we deployed additional decoys – this time decoys that are also vulnerable to the Log4j CVE. They were immediately noticed. Quickly, we identified that a high percentage of attacks on these were related to this CVE. There was a difference between the various geographical regions where the decoys were deployed, but overall, between 15-40% of the attacks on HTTP decoys were related to the Log4j vulnerability.

Attack Vectors – Injection Locations

Typically, an adversary tries to inject the target payload as the first part of the attack vector.

This vulnerability is unique in that any log action can be susceptible. Although there are a lot of similarities between web applications, each application will typically decide to write different logs in different conditions. Since the attacker does not have detailed knowledge of its victim’s application, the adversary tries to find which input fields are logged and in which conditions.

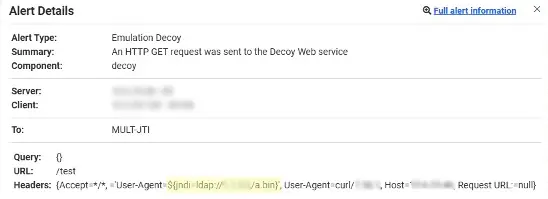

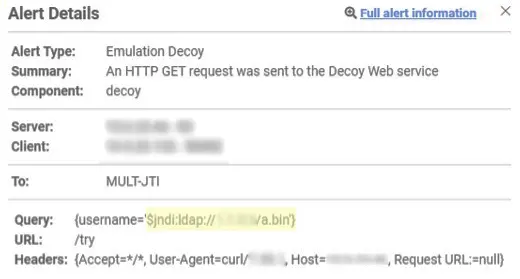

In the alert examples below, you can see the different locations that the attack can be placed.

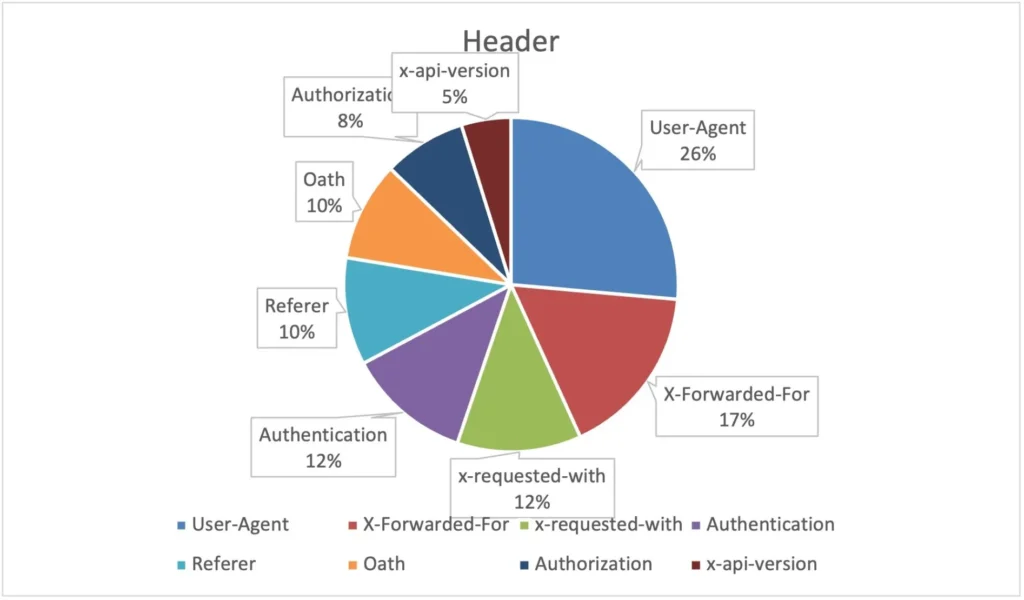

Next, we plotted the different locations that were used for injecting the vulnerability in the pie charts that follow. The most common attack vectors we noticed were HTTP headers. Within these, the User-Agent header was the most common exploit location.

Attack Vectors – Malicious Activity

The next part of understanding the adversary through deception decoys is to determine what the adversary is trying to accomplish once a compromise is detected. Most of the activities we identified were Recon driven – the attacker requests the victim machine to send some sort of notification that it can be compromised – equivalent to a ping.

Most of the attack attempts used the ping mechanism to identify the vulnerability. We did identify that about 30% of the attacks attempted additional actions, i.e., code execution attempts. (We will review those actions in detail in a follow up blog.)

In about 80% of the attacks, the attacker requested to send a ping to the same IP used for the attack injection. In other cases, we noticed the attacker tried to send the communication ping to a different server. Our analysis on some of those showed the attackers used proxies for the attack injection and then requested the vulnerable system communicate with a different server, a standard modus operandi for many attackers.

LDAP was usually used for the communication mechanism, while in some cases (under 6%) DNS was used to communicate, which we address next.

Evolution of the Attack

Using the data received by the decoys, we also noticed the attack evolve over the last few days. On the first day, most of the attack attempts were using the User-Agent header, which is very similar to the POC that was published. In the following days, we started seeing other, more advanced, methods.

The more advanced methods we saw included using another protocol for communication (DNS), encapsulating data to try to bypass HTTP/S signatures that were written and the use of additional headers, which are less popular.

Deception within the Enterprise

The Log4j vulnerability is generating headlines because it is both easily exploited and available in a wide range of applications. However, there are many vulnerabilities detected every day, most of which are about less popular software and harder to exploit.

Deception placed within the enterprise can be an early warning system for attempts to exploit vulnerabilities within your network. They can find attempted exploits against your installed software (CVEs) as well as configuration problems that can lead to attackers toward valuable data to steal or corrupt.

We have shown the results of placing decoys in the public domain for Log4j within the first few days after the announcement. Similar results are typical with every CVE announcement as attackers try to quickly exploit unpatched systems. Before vulnerabilities are published, many attackers share this information, which leads to zero-day exploits. This is where deception can also be a very effective detection and defense solution.

To summarize, we’ve outlined how the high-fidelity alerts characteristic of deception technologies make them an ideal early warning and detection system. We covered the initial data from attacks that reached public decoys. We’ve also shown how deception technologies within your organization detect nefarious behavior on your network early in the attack lifecycle. In addition to detecting attack activity, it allows you to safely monitor adversary behavior to learn more about their TTPs and likely next steps. This learning enables defenders to more effectively neutralize the threat while blocking recurrence.